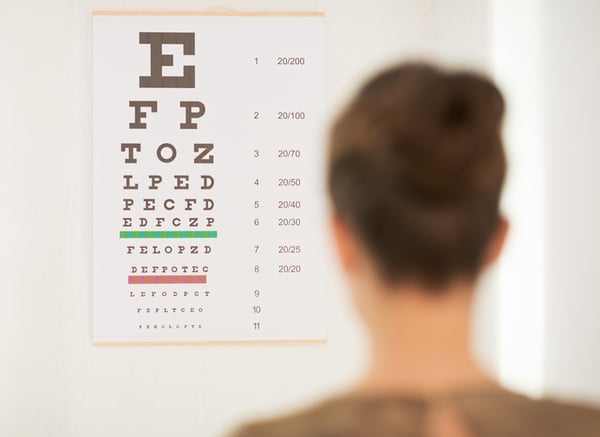

Parents and children are quite familiar with the eye chart used by most schools for vision screenings. It’s called the Snellen chart, and it’s given us the term “20/20” vision.

Unfortunately, 20/20 vision only refers to acuity, which the Snellen chart helps measure. This eye test does not detect a wide range of other vision issues that can result in a learning problem.

Can the Snellen Chart Detect a Learning Problem?

Many vision screening tests performed in schools are confined to the Snellen chart. Developed in 1862 by the Dutch ophthalmologist Hermann Snellen, the chart is used to measure visual acuity, defined as the visual ability to resolve fine detail.

On the chart, the first line consists of very large letters, and subsequent rows have an increasing number of letters that decrease in size. The smallest row that can be read accurately indicates the visual acuity of the eye.

The most familiar acuity test places the test at a standard distance of twenty feet. At the bottom of the chart is the 20/20 line. A person with 20/20 vision can accurately read this line while standing at the test distance of 20 feet.

A person with 20/30 vision would not be able to see the 20/20 line at 20 feet and instead would read the 20/30 line, which is two lines above the 20/20 line, and has larger print.

A person with 20/20 vision could read the 20/30 line at a distance of 30 feet, while the person with 20/30 vision would have to move up to 20 feet in order to see it.

This is a time-tested way to determine acuity. But can it detect other types of vision skills - ones that, if problematic, can cause a learning problem?

Vision Problems Missed by Snellen Chart

According to developmental optometrist Dr. Kellye Knueppel of The Vision Therapy Center, the Snellen chart is very useful for detecting near-sightedness. However, it’s profoundly lacking in other areas.

Besides not being very useful for detecting farsightedness, the Snellen chart often does not detect astigmatism, eye teaming difficulties and/or a ‘lazy eye’. All of these factors can cause a learning problem.

“If a child’s eyes don’t work together well it can cause great difficulty with tracking the lines of text across the page of a book or a computer screen,” Dr. Knueppel explained. “The Snellen chart doesn’t test for this.”

Even worse, Dr. Knueppel notes that the eye chart is susceptible to cheating. In the cases of adult patients worried about losing driving privileges, or children worried about wearing glasses, patients can often remember the sequence of letters, and then repeat them back when an alternate eye is tested.

“I’ve even had patients peek without knowing they are doing so,” Dr. Knueppel recalls.

Acuity Just One Part of What Can Cause a Learning Problem

Acuity is an essential part of vision, Dr. Knueppel points out, but it is only one component of a healthy visual system. The visual system includes the eyes, the brain and all the visual pathways. For effective vision to take place, all of these physical components must work together, helping a person utilize vision and make sound judgments based on what they encounter.

A learning problem, for example, may occur in someone who tests 20/20, but has a binocular vision disorder that won’t allow their eyes to work together when reading. This is the reason so many vision problems go undetected. The testing simply is not far-reaching enough to tap into all the vision problems that can affect learning.

Dr. Knueppel finds that many teachers, school nurses, physical therapists and learning disabilities professionals are shocked to discover that a child with 20/20 visual acuity can have a profound vision problem, and subsequently, a learning problem. “It’s surprising, but 25% of children have a vision problem that can affect learning,” Knueppel said. “Reliance on the Snellen eye chart for vision screenings is why the vast majority of these problems go undetected.”

What Should a Vision Exam Include to Help Pinpoint a Learning Problem?

A comprehensive approach is critical when testing for eye issues. In addition to visual acuity, she believes the following items must be included in the testing process: Alignment of the eyes, binocular depth perception, eye movements necessary for reading (‘tracking’), magnitude and flexibility of accommodation (‘focusing’), visual motor integration and visual perceptual abilities. “From there you can start to narrow in on a particular vision problem, if one exists,” Dr. Knueppel points out.

The problem with this wide range of tests, as opposed to the limited screening conducted at school, is that school staff doesn’t have the training or the equipment necessary to conduct the tests. It’s why Dr. Knueppel believes that understanding the symptoms behind typical vision problems is critical for parents and educators.

“If you see a child rubbing his or her eyes, avoiding reading, getting close to the book when reading or complaining of headaches or eyestrain, it should be a warning sign that more testing is needed,” Dr. Knueppel said. “From that point, the burden is on the parent to act and help uncover the true source of the learning problem.”

Knueppel recommends finding a developmental optometrist that pairs with general practice optometrists. “Generally speaking, an optometrist can perform the tests required to spot the problem, but often don’t have the time or equipment to do so. Parents will need to ask specifically whether or not the optometrist does all the tests needed to rule out functional vision problems,” she said. “In 25% of the cases, you’ll probably need to visit a developmental optometrist for a functional vision exam.”